Fifty-eight percent of all food produced in Canada is lost or wasted each year

And, one in eight Canadian households experience food insecurity – they don’t have consistent access to affordable, nutritious, culturally appropriate food. However, in Canada the dominant solution to feeding hungry households relies on grocery stores and consumers to make donations of food that is undesired or unsellable to charitable organizations such as food banks.

This is not a sustainable solution for many reasons. For one, it depends on the production of excess and the generation of “waste,” which is inherently inefficient treatment of a precious resource. It also does not preserve the dignity or choice of people accessing the food. And it does not respect the labour of people in the food system who had earlier toiled to produce the food subsequently labelled excess or “waste”.

What is a just circular economy of food, anyway?

It’s a simple concept. In a just circular economy of food, waste doesn’t exist and every person has access to healthy, nutritious meals. But it’s far easier said than done – and in order to build a circular economy food system, we must first understand the existing landscape, identify gaps and opportunities, and build an action plan.

A “Right to Food” Framework for a Just Circular Economy of Food

For the most part, previous attempts to address food waste and food insecurity have generally focused on retail and consumer behaviours. However, focusing on one end of the food supply chain puts all the responsibility of reducing food waste onto private enterprises, non-profits, and charities that have limited capacity to alleviate the root causes of what are – let’s face it – systemic issues.

With support from Mitacs, and the Economic Transformation Lab, Vancouver Economic Commission (VEC) collaborated with Simon Fraser University’s Food Systems Lab to undertake this research with a longterm goal of implementing a just circular economy of food in Vancouver. The resulting report, “A Right to Food Framework for Tackling Food Waste and Achieving a Just Circular Economy in Vancouver, British Columbia” distinguishes itself from existing research by incorporating a “right to food” principle as a framework for assessing solutions. For more on this framework, this handbook by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations provides further information about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights passed in 1948 recognizing the human right to food.

For the study, researchers interviewed participants with expertise across the local food system, and reviewed literature to build a theory of change for Vancouver’s food system.

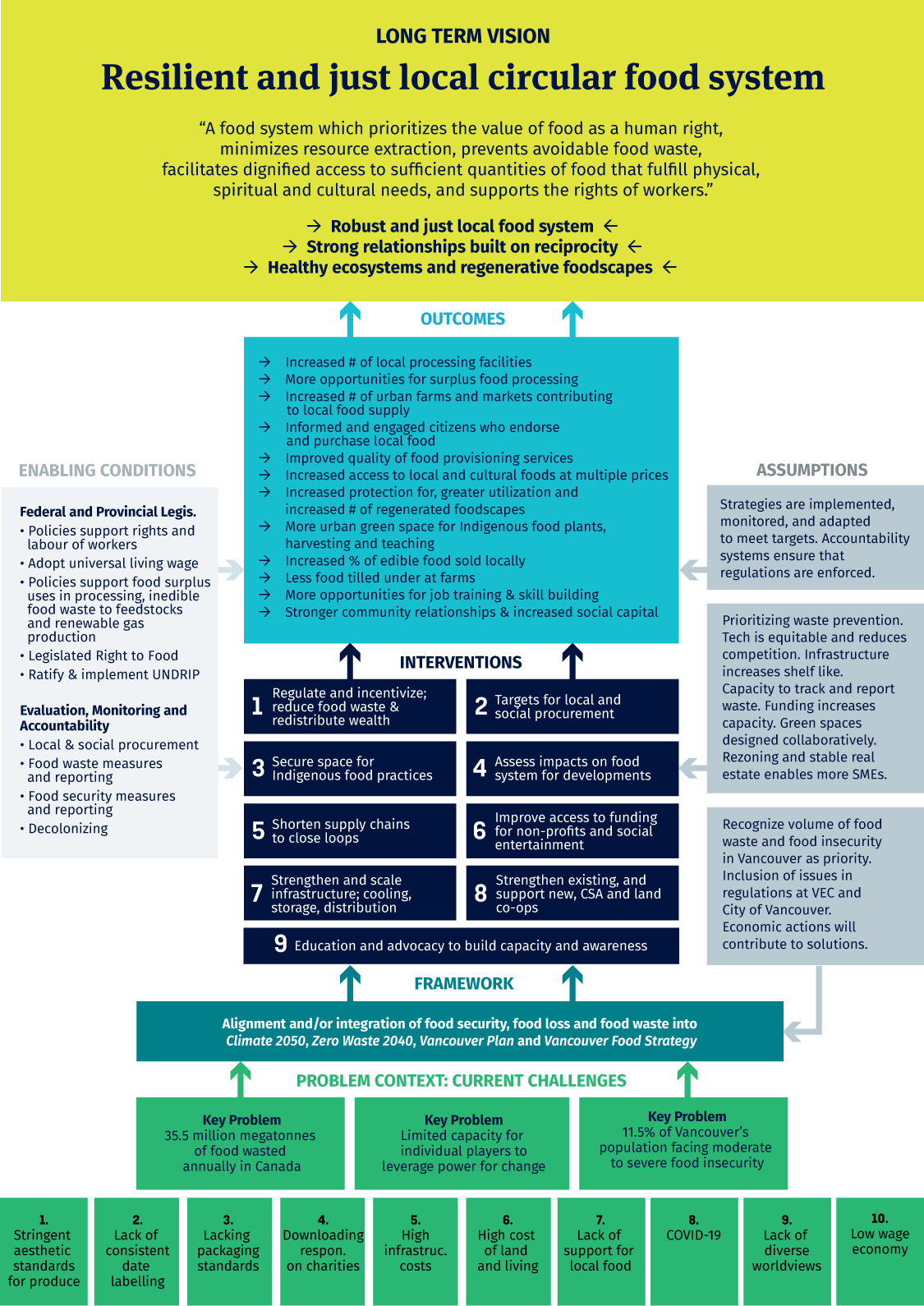

A theory of change is a thorough, illustrative model of how and why a desired outcome – in this case a just circular economy of food – could happen in a particular context.

The below diagram shows one of the products of the study: a theory of change that describes the key problems, policy framework, enabling conditions, interventions, outcomes, and long-term vision required for a just circular economy of food.

Figure 2: A Theory of Change for achieving a just circular economy of food

How do we take action towards a circular economy of food?

To introduce a just circular economy of food, we first need to explore intersecting challenges for food systems agents and prioritize interventions that address food waste and food insecurity as being inextricably linked.

There are three necessary pillars of a resilient and just circular economy of food:

- Robust local food supply chains

- Strong relationships built on reciprocity

- Healthy ecosystems and regenerative foodscapes

Actions to advance a just circular food economy should align with “right to food” principles that uphold the dignity, agency and choice of consumers. Actions should also align with, or – even better – be integrated into policies for reducing food waste, increasing food security, increasing climate resilience, and fulfilling municipal and regional planning. The most relevant regional policies and strategies consulted for this study include Climate 2050, Zero Waste 2040, Vancouver Food Strategy, and the Vancouver Plan. The following actions were synthesized from review of these policies, interviews with food system agents, and insights from the project advisory group.

Provide ongoing and sustained support to individual just circular economy of food efforts to leverage their power for greater impact. Support that takes the form of funding, infrastructure, permitting and policies will be particularly valuable in leveraging efforts by food system participants, and other actors.

Adopt transparent accountability systems for key activities in a just circular economy of food. Transparency and accountability to the food system should be adopted in local and social procurement practices; food waste measurement and reporting; and food security measurement and reporting.

Advocate for a just circular economy of food based on the “right to food” principles. This means advocating for provincial and federal legislation that supports:

- The rights and labour of agricultural workers;

- A universal living wage

- Food safety policies that facilitate circular practices; and

- Implementation of the Right to Food, following through on commitments to create an action plan for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

What does building a just circular economy of food look like in practice?

Here are nine key action areas where well-planned initiatives could lead to a sustainable and lasting just circular economy of food.

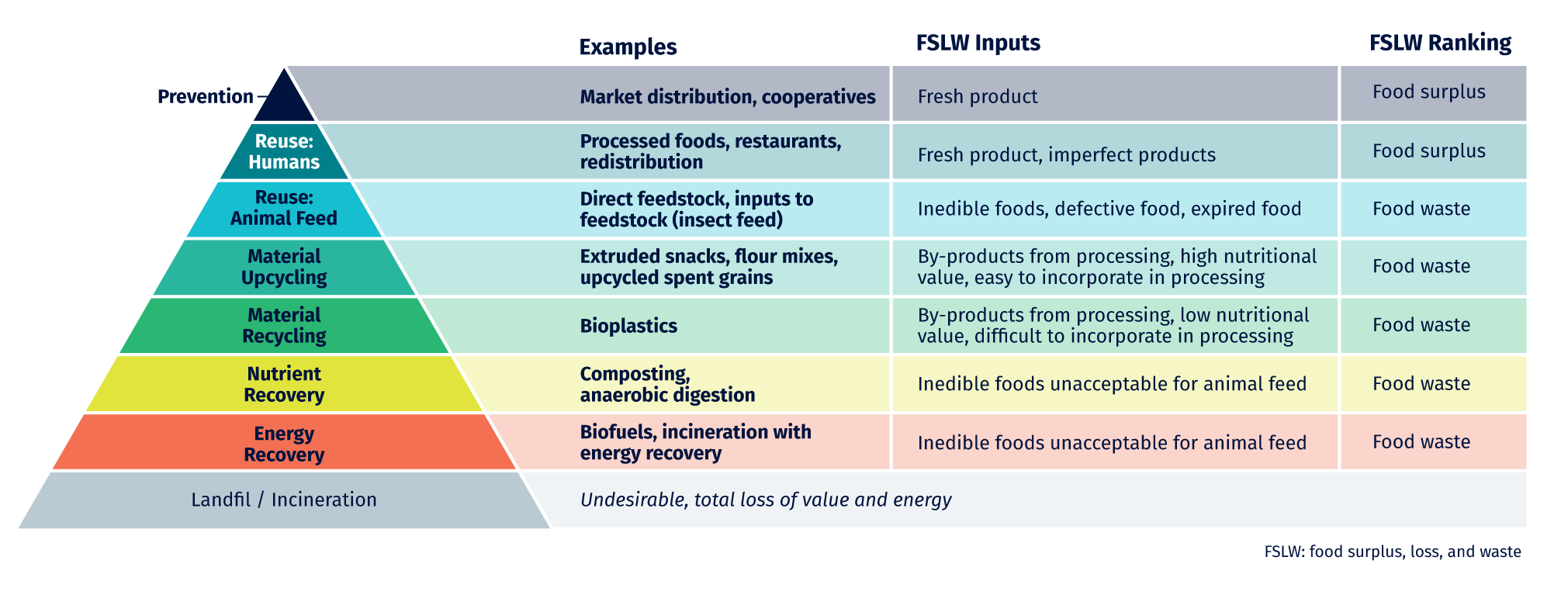

- Adopt clear regulations and reporting based on a food waste prevention hierarchy that differentiates between categories of food surplus, loss, and waste (FSLW), and prioritizes closing loops leading to FSLW

- Adopt concrete targets for local and social procurement of food and other categories

- Secure space to grow, preserve, and harvest Indigenous plant foods and medicines

- Assess impacts on the local food supply chain as part of future land developments, and ensure affordable spaces for food production and processing remain accessible

- Shorten supply chains to close loops on non-organic and organic packaging materials

- Improve access to funding for non-profits and social enterprises to adapt services to community needs and implement circular economy practices

- Invest in infrastructure for cooling, storage, processing, and distribution that can be accessible to NGOs and local farms

- Strengthen existing, and advocate for new, community-supported agriculture programs and land co-ops to shorten the distribution chain from farm to consumer

- Advocate and educate to explore non-commodity values of food, empower citizens and build social infrastructure that supports poverty reduction and amplifies food waste awareness

Onward to a future of sustainability and food security

Ultimately, this work envisions a circular economy of food that reduces resource extraction, keeps materials at their best and highest use, and upholds equity and justice. With an established framework and tangible action underway, Vancouver can take the important initial steps towards a circular economy of food that solves two systemic challenges at once: food waste and food insecurity.

Figure 2: Progressive food waste prevention hierarchy diagram.

This diagram is adapted from Teigiserova et al., 2020, page 5.

A “Right to Food” Framework for a Just Circular Economy of Food

In Canada, 35.5 million megatonnes of food are wasted each year. And, one in eight Canadian households experience food insecurity. Meanwhile, the most common attempts to solve food insecurity aren’t working. So, how do we move forward? See the recommendations in this new report.